Last Updated on November 7, 2024 by Angel Melanson

In 2024, the Saw franchise feels like something of an anachronism. Saw X, the series' 2023 return to form after a period of false re-starts with Jigsaw and Spiral: From the Book of Saw, finds Tobin Bell re-donning the robes of the infamous Jigsaw killer for a nostalgic, throwback entry that nonetheless adds some fresh new wrinkles to the established formula: a South American setting, a sleeker, more toned down style, and Synnøve Macody Lund as a baddie who can actually go blow-for-blow with Bell's torture-happy civil engineer, John Kramer.

But even with this new tack, there's no escaping that the series belongs to a different era, one in which spectacle murder was available at the cinema and not as an inescapable fact of daily life.

One need only scroll their social media feed to see what's changed between now and 2004, when James Wan and Leigh Whannell took Sundance by storm with the film that would spawn the long-running franchise and almost single-handedly usher in a gritty new wave of horror filmmaking.

Earlier this year, a 32-year-old Pennsylvania man allegedly decapitated his own father before posting a fourteen-minute video to YouTube in which he showed off the plastic-wrapped cranium while railing against the current presidential administration. That clip sat on the video platform for around six hours in flagrant and unambiguous defiance of its terms and conditions before being taken down – racking up thousands of views. Its eventual removal – especially with such delay – did virtually nothing to slow the gruesome video's spread, with clips and screenshots flooding social media platforms.

Despite all this, the images made little impact outside the chronically online sphere, with nary a peep from news websites which, if they did cover it at all, did so with a now-familiar dispassion. And it's easy to see why: suicide, death, and dismemberment have gone increasingly online since Saw's heyday, supplanting whatever shock audiences used to feel with something resembling cold, resigned disinterest.

Murder as spectacle has existed as long as humankind – from the Roman Colosseum to public lynchings in the United States – but at the dawn of the 21st century, violence went visibly global for the first time with the events of September 11th, 2001: giving rise to a political climate of paranoid hysteria and generations of American viewers who were irrevocably marked by the spectacle of mass death broadcast live into their living rooms.

This attack came directly in the wake of the massacre at Columbine High School in April of 1999, a similarly era-defining terrorist event that held America spellbound and announced a grim new dawn for mass shootings in spaces (schools, supermarkets, places of worship) once considered to be safe. Though the word “spectacle” (defined by Merriam Webster as “something exhibited to view as unusual, notable, or entertaining, especially: an eye-catching or dramatic public display” or “an object of curiosity or contempt”) is often synonymous with entertainment, it's also an essential part of what sets terrorism apart from other forms of murder.

In his book Columbine, journalist Dave Cullen cites the work of sociology professor Mark Juergensmeyer, who defines terrorism as “performance violence,” or atrocities that are meant, by their very nature, to be seen by the largest audience possible – i.e. spectacles.

Though terrorist acts are ideological or political by definition, in the 21st century, such acts are increasingly purposeless, mere spectacle, or, as Cullen puts it: “performance without a cause.” These words help define not just the two acts of public mass murder that kicked off our current century but also the cinematic movement that followed, “Torture Porn,” which is often cited as a cinematic trauma response to the horrors of 9/11, the pyrrhic victory of the so-called War on Terror, and the crimes committed by American soldiers at Abu Ghraib prison.

Regarding these films, David Edelstein, in the 2006 New York Times article in which he (still controversially) coined the phrase “Torture Porn,” sums it up succinctly, saying: “Some of these movies are so viciously nihilistic that the only point seems to be to force you to suspend moral judgments altogether.” Oxford University film professor Nikolaj Lübecker takes it even further, writing of Bruno Dumont's masterfully sickening 2003 feature Twentynine Palms: “Instead of watching a work in which the three strands [political, physical, metaphysical] organically combine, we experience an implosion of meaning.”

In the same way that Saw, Hostel, or any number of these films elide or outright implode meaning with their floridly detailed performances of simulated brutality, the past twenty-four years of senseless, often random acts of public violence have done for a chronically disenchanted American populace.

“Fear supplants empathy and makes us all potential torturers, doesn't it,” Edelstein rhetorically asks in his aforementioned piece, which concludes with a cheeky, “Was it good for you, too?”

Though the violent tortures are almost without purpose by design, it's hard to discount the assertion that the films sought to exorcise a culture-wide fear of threats from outside through onscreen acts of extreme cruelty, even while making viewers complicit in the acts depicted. Essayist Catherine Zimmer sees a strong sense of irony in these films' penchant for offering young (mostly white) people abducted, tortured, and killed by nefarious foreigners to a young (mostly white) audience, declaring it a “tremendously projective fantasy – one in which American youth are figured as the victims rather than perpetrators of this kind of organized violence.”

This rings especially true decades removed as we are from the 2000s when everyday gun violence has eclipsed all other causes of death as the single greatest threat to American youth, to say nothing of our country's destabilizing and interventionist policies that do untold damage to societies abroad.

Interestingly and in contrast to many of his brethren, the Jigsaw Killer is a homegrown domestic terrorist who adheres to something of a warped moral code; it's all too easy to imagine John Kramer leaving a cracked, rage-filled manifesto to make the rounds online. Yet the spectacle in Kramer's murder methods is only extratextual – though spectacular violence is being performed for us, the audience, within the world of the films, these extravagant methods of murder are mostly contained in warehouses and largely intended to be seen only by the perpetrator himself and the police.

One of the only times that this formula is broken in the oddly prescient cold open of the otherwise forgettable Saw 3D, which sees the two-timing Dina (Anne Greene) suspended above a whirling circular saw steered by her confused boyfriends (Sebastion Pigott and Jon Cor). The setting makes the scene unique: the three lovers are on display in a glass box in a busy public square for onlookers to ogle. The intergenerational crowd barely attempts to rescue the doomed trio before whipping out their mobile devices to record the carnage.

As the (at the time) final chapter in the Saw franchise, this feels like an honest metafilm reflection on the gruesome entertainments the series had doled out up to that point, holding up an audience of eager, screaming onlookers as a mirror reflection of those who had returned yearly to see what new violent spectacle Jigsaw had in store from 2004 to 2010.

But how has the Saw series changed to reflect our new normal since then? After two bungled attempts at relevancy, Saw X takes things back to basics while uniquely subverting old themes in ways its makers are perhaps not entirely conscious of.

The first of these addresses Zimmer's assertions of white victimhood: the characters of Gabriela, Diego, Mateo, and Valentina (played by Mexican actors Renata Vaca, Joshua Okamoto, Octavio Hinojosa and Paulette Hernández) are each complicit in the plot to defraud John Kramer with the promise of a bunk life-saving brain cancer cure, but do so at the behest of Macody Lund as Dr. Cecilia Pederson, an affluent Norwegian woman who has moved her operation from her home country to South America, and escapes mostly unscathed while her cohorts meet their ends in their respective traps.

Though the messaging is likely unintentional, in Saw X we see not only an example in micro of white imperialism and its deleterious effects on citizens of developing nations but also a subconscious acknowledgment that whiteness, contrary to what those of us who grew up in post 9/11 America were lead to believe, is largely insulating, with marginalized citizens bearing the brunt of the country's epidemic of gun violence.

Saw X also foregrounds its characters while treating its torture setpieces as secondary. This was also the approach in Spiral, but producers Mark Burg and Oren Koules learned their lesson. Realizing the franchise was a wheel that didn't need re-inventing, they decided to give audiences what they wanted since way back in 2006, when Saw III made the instantly regrettable mistake of killing off not just John Kramer, but also his fan-favorite apprentice, Amanda Young (Shawnee Smith).

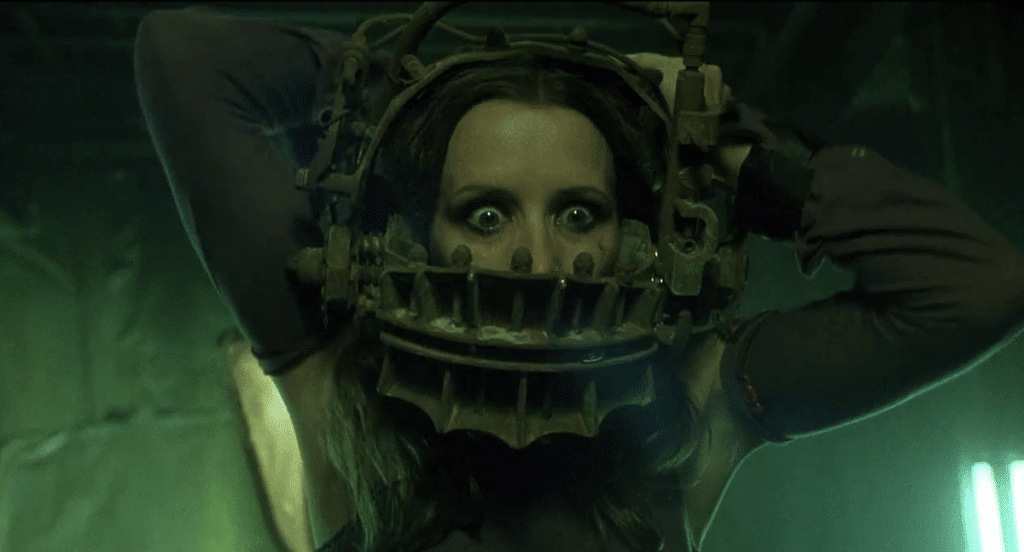

With all due respect to Costas Mandylor, latter entries in the original series struggled to find suitable replacements for that dynamic duo. Saw X allows their relationship to take center stage once again. Add in the previously mentioned Macody Lund as an instantly iconic foil for Kramer, and Saw X prioritizes human interaction in a way almost every single entry leading up to it fumbled. That isn't to say that the death set pieces aren't impressive (though they're worlds away from the flashy operatic spectacle of the “Angel Trap” or “Carousel of Death”), but audiences who showed up for gore in the 2000s want something more to chew on than paper-thin characters choked down with buckets of blood in the 2020s.

This renewed focus on character also expands upon Kramer's flawed antihero status. Much has been said about the problem of the character's so-called “philosophy” as a torturer, as he truly believes that he's doing a favor to those very few who manage to escape his traps and denies responsibility for the deaths of those who can't. Wan's original film does set up Kramer's ethos. Still, it views him as a villain, even though, over the course of the series, he has been elevated to something like a folk hero.

This journey is completed in Saw X. Taking a cue from Don't Breathe 2, the film adds some heroic facets to Kramer by contrasting him with villains the film considers worse, weirdly attempting to reverse the very implosion of meaning this subgenre is known for. It's a softening of a character who started as a self-aggrandizing monster into an agent of some sort of moral good; as the violence outside the walls of our movie theaters has grown more senseless, the franchise has responded by solidifying its moral core, no matter how warped or absurd it may seem.

In some ways, the antithesis of Saw X's search to give meaning to its violence – or the inheritor to its original ethos – can be found in Pascal Plante's excellent 2023 feature Red Rooms, which gets its title from the myth of dark web torture chambers where internet users can watch real-world murder on demand.

The notion that such places actually exist has mostly been debunked as urban legend, but the concern dates back to the earliest days of the internet and has been tackled in film previously (Olivier Assayas's Demonlover specifically). Though Plante makes the phenomenon frighteningly and viscerally real, the idea feels out-of-step and even passé with the current realities of the internet. Even without dark web access, the average internet user is mere clicks away from as much violent content as they can stomach, no Tor browser needed.

Active participation, of course, remains elusive, but search “Livestreamed Crime” on Wikipedia and marvel at the list of incidents beginning in 2008 that has grown each year since then with beheadings, suicides, and mass shootings committed live on platforms unwilling or unable to combat the issue.

And that's to say nothing of footage of incidents posted after the fact, whether it be videos taken moments before the bloodshed began at Pulse Nightclub immortalized on Snapchat or images of scared crowds fleeing as shots ring out across multiple cities in the U.S. on every major holiday and occasion, the most recent being the chaos of a Kansas City parade that celebrated their hometown team's 2024 Super Bowl win. Terror has become a way of life, and it's no exaggeration to say that the 9/11 hijackers or student-killers of Columbine would be frothing at the ease with which they could spread their atrocities across the internet in 2024.

As Saw hits the two-decade mark, Saw X shows that there's still something to a franchise that once offered the types of violence we collectively reeled from in the wake of unfathomable national tragedy. But the violence hasn't stopped. It's only grown in the decades since, and we must ask ourselves: what fear is there in strangers tormenting you in isolated warehouses for moral sleights when you can be killed in plain sight for no reason at all?

What separates the gruesome tortures of John Kramer from what lurks beside seemingly benign hashtags? The Saw of now differs from the Saw of two decades ago, which funneled our national fears and angst into a gruesome terror spectacle, reconstituting into a form we could digest more easily.

Saw in 2024 is a holdover over a bygone era that, in an ironic twist, seeks to provide comfort through nostalgia for an era when violence was a novelty rather than a norm. And though many of us still have yet to be touched by the horrors flooding our feeds, we're affected just the same.

We feel its weight in our guts, in the deepest parts of ourselves: a fear that can no longer be expelled by a trip to the cinema because there's just too much of it. We can only stare unblinkingly, our noses pressed against a glowing pane of glass, doing our best to avoid the slow drip of horror infiltrating our carefully cultivated social media feeds. And should we see a plastic-wrapped head, or prone and bloodied parade goers, or the remains of a child blown apart in a conflict a world away yet right inside our retinas, what options do we have? Block and report, or repost and spread the spectacle of fear like sickness.