Last Updated on July 9, 2025 by Amber T

This article contains spoilers for 28 Years Later.

Last year, I had the pleasure of attending the great Fantastic Fest in Austin, Texas, where one of the surprise screenings was none other than the Robbie Williams biopic Better Man. As one of the only Brits in the crowd, I sat enraptured as an air of bewilderment settled over the seats of the Alamo Drafthouse, watching an audience of Americans learn in real time who Williams, one of the UK’s biggest popstars but virtually unknown to our transatlantic cousins, is and why on earth he should be deserving of a 134-minute film in which he is also, for some reason, depicted as an ape. When the credits rolled, I braced myself to field off the questions from curious peers: who was that guy? Why did he take his skin off in that one music video? Why did the British public love him so much?

During my screening of 28 Years Later, this familiar feeling overtook me again, and I was struck with a sudden, terrifying realization. Oh no, I thought to myself, I am going to have to explain to my American friends who Jimmy Savile was.

It’s been 28 years since the apocalypse laid waste to the United Kingdom, and 23 years since Danny Boyle changed the game of modern horror with 28 Days Later, introducing the world to a new form of ‘zombie’ (yes, yes, infected), one resurrected by rage and all together far too alive. While pulling liberally from distinctly non-British media like Romero’s Night of the Living Dead and the Japanese (but American inspired) Resident Evil games, 28 Days Later owed plenty of its success to the fact it is utterly, beautifully, horribly British. It’s a dirty word to many – and rightfully so in many instances – but believe it or not, there once was a time where this little nation made some of your favorite horror movies: without even scraping the surface of Hammer’s vast oeuvre, there’s The Descent, Shaun of the Dead, The Wicker Man, Hellraiser, The Devils and Saint Maud to name but a small few. Needless to say, with their return to a film so inextricably tied to the UK, the pressure was on for Boyle and writer Alex Garland to deliver a shot of adrenaline to the heart of our gasping industry, to remind people that Britain can (and god willing, still will) make great horror cinema. Whether or not 28 Years Later succeeds in doing so will be a point of contention, critically at least – this is a film guaranteed to be one of the most divisive of the year, and much like a certain British yeast-based spread, you will either love it or hate it. After all, if Brexit taught us anything, it’s that we’re a nation sharply divided. In this writer's humble opinion, 28 Years Later could well stand to be the best horror movie of the year, and while I'm not sure I'd agree that it's the best in the franchise, it's a damn worthy second place.

Those expecting a 28 Days Later clone from this brand new trilogy starter will be disappointed, but that’s on you. 28 Years Later is a different beast entirely, and as it should be – the face of Britain is a much different one than it was almost three decades prior. It’s a face disfigured by the trampling of boots, boots, boots (marching up and down again), a face twisted by three decades of austerity rule, three decades of gutted social services, three decades of the poor getting poorer, the rich getting richer and the sick getting sicker, three decades of playing lapdog to a country that wouldn’t piss on us if we were on fire. While 28 Days was a brutal and bleak reflection of an anxious Blairite Britain teetering on the precipice of promised world destruction with 9/11 barely in the rear view mirror, 28 Years Later situates us comfortably up the creek without a paddle. The damage is done, the world has already ended. All our survivors – Aaron Taylor-Johnson’s Jamie, Alfie Williams’ Spike and Jodie Comer’s shatteringly tragic Isla – can do is make do and mend.

The Britain of 28 Years Later is as wistful as it is a warning – Boyle’s Holy Island Mission stands as the logical end point of a nation driven deranged with returning to the ‘glory days’ of the Empire. Part Pagan cult and part village fête, the island is at once both cloying and comforting in its familiarity. It’s Threads meets The Good Life, the twee sensibilities of wartime Britain perversely out of place in a world that has evolved and left us long behind in an undignified past of bootstraps and butter rations, bullets and bandoliers. Indeed, one of 28 Years Later’s most suffocatingly intense scenes comes not from the onslaught of Infected but from the inebriated cheers of well-meaning locals drunk with the promise of a hero sent to save them, the softly sneering face of Her Maj, whose leadership is nowhere to be seen, looming serenely over all – just in case you forgot that Boyle is a constitutional republican who refused a knighthood. That the Holy Island should celebrate violence, encouraging brutality from its would-be giant killer (rather than, say, the intelligent and gentle guidance of Ralph Fiennes’ Dr Kelson, deemed insane by the community’s patriarchs) feels particularly poignant on the other side of more than a few misguided democratic decisions in the last three decades.

The idea that Britain would be shut off from the rest of mainland Europe was a laughable one 2002; in 2025, it’s a troubling reality – and worst of all, it unfolded voluntarily. The emblematic stench of Brexit is all over 28 Years Later, coming most notably with the introduction of Swedish soldier Erik (Edvin Ryden), who, as the European observer, is horrified by the notion of being trapped on this isolated island with these deranged savages, and the Infected too. And while the Infected of 28 Days Later represented the primal fear of societal breakdown, the Infected of 28 Years Later stand as a more evolved threat reflective of our current situation – they are in power now, and they are simultaneously pitiful and more frightening than ever. The gluttonous Slow Lows in particular feel like a reminder from Boyle that you can’t turn your back on any of them for even a second – even the ones that seem harmless. The sentiment calls to mind visions of the buffoonery of floppy-haired Boris Johnson, paragliding into the Olympics, a limp Union Jack clutched in each fist. Like the Slow Lows, we as a nation underestimated the danger of this particular brand of benign British eccentricism, and look where it left us.

Amidst the feverish madness however, there’s an undeniable hardiness to this close-knit community that is in many ways quite appealing – the simplicity of rural living in a world reset to year zero, a world without the Internet, office jobs or bloodsucking billionaires. In sharp contrast to the urban decay of 28 Days Later’s London setting, 28 Years Later depicts a world in line with the universally accepted yet existentially troubling truth that the earth would be far, far better off without us. Anthony Dod Mantle’s sweeping shots of vast hillsides untouched by agricultural destruction and lush greenery peppered with lavender and gorse (the recent felling of Sycamore Gap’s tree, a centerpiece of much of Years’ visual splendour, becomes even more tragic when placed in the context of this story) boast the best of Britain’s natural beauty, something we can still be proud of. Because 28 Years Later is not a film that hates the country that birthed it or the people within it, far from it. It’s an impassioned plea to remember what could really make this country great, demonstrated by Kelson in all his iodine-soaked glory. Empathy, humanity and respect for all, but especially those abandoned and left to rot by the country supposed to protect them. In a cinematic landscape all too saturated with irony poisoning, eye rolls and clanging insistence that the filmmakers are just as in on the joke as the audience, 28 Years Later is deeply refreshing in its sincerity. Those uncomfortable with the earnestness of the film may wish to remind themselves that 28 Days Later was also, above all else, a film about humans killing humans – and in its intended form came with a heart-swellingly ‘soft’ ending that also infuriated viewers.

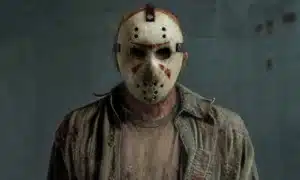

Speaking of endings, the final five minutes of 28 Years Later are already proving to be the talking point of the year, with the appearance of a hooting and hollering Jack O'Connell (fresh off his take on another twisted little freak in Ryan Coogler's Sinners) inexplicably dressed as one of Britain's most notorious pedophiles, tracksuit and all. While the specifics of Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal’s motley crew of survivors will remain a mystery until, presumably, the next entry in the trilogy, there’s still plenty of thematic meat to chew on. Canonically, the virus ended British civilization before Savile’s crimes ever came to light – it’s entirely possible that Jimmy is still clinging to the decaying vestiges of his childhood hero (because if you think the end of the world won’t be marked by adults wearing silly costumes of a past they should’ve long shed, take a stroll through King's Cross Station on any random Tuesday to see J.K. Rowling’s TERF army lining up for pictures at Platform 91/3 quarters…) But as there is perhaps no pop cultural icon who represents the pervasive rot of Great Britain more than Savile, O'Connell's scene-stealing grin and command over his maniacal minions does not bode well for our survivors, nor does it bode well for the future of a fledgling society that should be moving forward into greener pastures, not back into stagnant nostalgia for a past long vanished. From our brief interaction, it seems Jimmy is a lost boy clinging desperately to the hand of a predator for misguided guidance – a sentiment that could well be applied to the civilians of any nation. Some may see the ending of 28 Years Later and its Teletubby metal showdown as ludicrous, sure, but these are ludicrous times we are living in. And ludicrous times, after all, call for ludicrous wigs and garish gold rings. Either way, it will be exceedingly interesting to see how an American director like Nia DaCosta grapples with the Jimmy Crystal of it all in The Bone Temple – and I’ll be seated Day One to find out.

For our exclusive chat with 28 Years Later FX maestro John Nolan, make sure to grab the upcoming issue of FANGORIA.